The Tanka of Eishin-ryū: Part 4 – Ukigumo (revised)

31 December, 2009 by Richard

In this series of articles, I am attempting to translate and contextualise the dōka of Hasegawa Eishin-ryū. All articles in this series can be found here. This article covers the tanka for the fourth technique, Ukigumo.

Yonhon-me: Ukigumo

'浮き雲 / a floating cloud' by furbychan on Flickr.

Ukigumo is the fourth technique in Hasegawa Eishin-ryū. The execution varies somewhat between Musō Shinden-ryū and Musō Jikiden Eishin-ryū, but the movement and feeling involved are much the same.

It is well-known that Hasegawa Eishin was an expert yawara (jūjutsu) practitioner. There is even a Hasegawa-ryū yawarajutsu that claims descent from him. The Hasegawa Eishin-ryū contains a good deal of grappling techniques, or techniques that may be effectively adapted for use in grappling, and Ukigumo is a prime example of this. Even without adapting the basic ’situation’ usually used to describe the waza, there are several clear grappling elements. The nukitsuke here may be treated not so much as cutting through but as applying the sword to the opponent. The sword is then used to take the opponent to the ground, where they are killed with a cut to a vulnerable area of the body.

Ukigumo means ‘floating cloud’ or ‘drifting cloud.’ It is an enduring image in Japanese poetry, notably appearing in a famous passage in the Tale of Genji. The Chinese word fúyún (浮雲), adopted into Japanese as fuun, has approximately the same meaning. The floating cloud is a metaphor for being restless and changeable. As with other imagery we have seen, it can also mean something ethereal or ephemeral that is liable to move or vanish.

Below is the waza as it appears in Musō Shinden-ryū.

As mentioned above, the execution and riai of the waza differs slightly between Jikiden and Shinden. There are two major reasons for this: firstly, Jikiden comes from Tanimura-ha Eishin-ryū and Shinden comes from Shimomura-ha; secondly, Nakayama Hakudo is known to have adapted the waza to some extent when he formulated Musō Shinden-ryū.

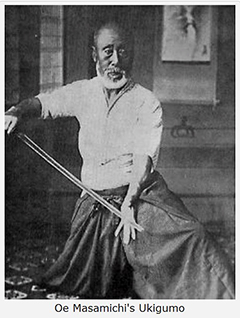

Oe Masamichi's Ukigumo

For completeness’ sake I will describe the waza as it appears in both schools. My description of the Eishin-ryū Ukigumo comes from my own training, whereas my description of the Shinden-ryū version is adapted from the Japanese edition of Musō Shinden-ryū Iaidō by Shigeyoshi Yamatsuta, a first-generation student of Nakayama Hakudo.

Musō Jikiden Eishin-ryū:

The practitioner is sat in a line: there is one person sat between the practitioner and his opponent on his right. The opponent moves to grab the practitioner’s tsuka, and the practitioner evades by standing and stepping to the rear left. He then steps in and crosses his left leg over the right. He raises his tsuka high and moves the saya close to his body, to move it out of the way of the middle person. The practitioner then lowers the tsuka and, pushing it left to ensure the middle person moves out of the way, he draws his sword, twisting his hips and dropping them low to make a shallow cut into the opponent’s shoulder. Placing his left hand on the back of the sword, he kneels and drags his opponent to the floor, face down. Raising the sword into furikaburi*, he steps on the opponent’s sword arm, sleeve or hakama and cuts deep into their back.

* Note that this furikaburi is out to the side in a kind of high hassō position. However this position is quite different to the usual kendo-style hassō.

Nakayama Hakudo's Ukigumo

Musō Shinden-ryū:

The single opponent is sat directly to the practitioner’s right. As above, the opponent attempts to grab the practitioner’s tsuka. The practitioner evades by standing and opening the body to the left. He then steps back in, without raising the tsuka, crosses his legs and draws the sword while twisting his hips, striking the opponent’s chest and right arm. Kneeling, the practitioner places one hand on the back of the sword and drags the opponent to the floor, face up. Returning the sword along the same line, he assumes jōdan no kamae, treads on the opponent’s arm or sleeve and cuts the torso.

As you can see, these waza are very similar, but differ slightly in execution because the reasoning behind them is a little different. In either case, however, the following tanka may still be relevant.

浮雲

麓より吹上げられし浮雲は

四方の高嶺を立ちつつむなり

Ukigumo

Fumoto yori

Fukiagerareshi

Ukigumo wa

Yomo no takane o

Tachitsutsumu nari

Floating clouds are blown

From the base of the mountains

Up to their summits

Rising to envelop each

Of the lofty mountain peaks

Firstly, a few notes on the language used.

The word ‘ukigumo’ itself is loaded with meaning. It is famously the title of Japan’s first modern novel, written in 1888 by Futaba Tei. It is a metaphor for not being tied down, and wandering – both physically and emotionally – “wherever the wind takes you.” This has an air of melancholy and loneliness to it, and when it is used in this way the word is often written 憂き雲: a play-on-words, literally meaning ‘melancholy cloud.’

In the Eishin-ryū tanka, there is an explicit description of a move upwards from a low position. This is in contrast to the tanka for Oroshi, which I will examine in my next article, but otherwise the two contain quite similar imagery in their opening lines. In the tanka above, clouds are blown by the wind from the base of the mountains. They settle from above upon the peak of each mountain, hiding them from view.

The word yomo (四方) used here is rather archaic. It means ‘all directions,’ or ’surrounding.’ The kanji are usually read shihō in modern Japanese, although the form yomo persists in some idiomatic phrases, such as yomoyama (四方山, ‘all kinds of things’). It is this word that indicates more than one cloud is described, as it indicates that many separate peaks are enveloped.

In The Tale of Genji, written c.1004AD, the chapter ‘Aoi’ famously contains the following poem. Whilst many English translations are available, the ones I have been able to find are all nicely contextualised by the surrounding text; therefore to make sense of this poem in isolation I will make a crude translation myself.

雨となりしぐるる空の浮雲を

いづれの方とわきてながめむAme to nari shigururu sora no ukigumo o

Izure no kata to wakite nagamemuHow can I find the plume of ash from her funeral pyre

Hidden amongst the floating clouds in this sky of showers?

Ise-no-Taifu

浮雲は立ちかくせども隙もりて

空ゆく月の見えもするかなUkigumo wa

Tachikakusedomo

Suki morite

Sora yuku tsuki no

Mie mo suru ka na

Floating clouds may move

To obscure the moon from sight

Yet we may still catch

Glimpses of it through the rifts

As it traverses the sky

There is also the relationship between the cloud and the mountain. A floating cloud is not fixed or held in any way and may move about the mountain, resting at different heights, depending on the whims of the wind.

The following is one of the shihai poems found on the Kanmon Nikki, which was written between 1416 and 1448 by Gosu Kōin. The paper on which these poems were written was reused to write the diary. As Japanese paper was valuable, it was often turned over and reused in this way. Writing that survives on the back of reused paper is known as shihai writing (紙背文書).

うきぐもは

ふもとのしぐれ

みねのゆきUkigumo wa

Fumoto no shigure

Mine no yukiFloating clouds bring

Showers to the mountain’s foot

And snow to its peak

Here, the clouds are changeable, not just in their movements, but also in their behaviour. This poem in fact suggests the clouds’ behaviour changes to fit their location, although this understanding may not necessarily stretch to how the image is thought of in Eishin-ryū.

Let us look at one more poem to contextualise Ukigumo, by Fujiwara no Ariie (1155-1216) from the Shinshūi Wakashū.

木の葉散るむべ山風のあらしより

時雨になりぬ峰の浮雲Ko no ha chiru

Mube yamakaze no

Arashi yori

Shigure ni narinu

Mine no ukigumoThe great mountain wind

Scatters the trees’ falling leaves

And brings floating clouds

That will not break in shower

To the peak of the mountain

Again, concealing clouds that are blown about on the wind, just as the leaves are. The floating clouds rise to envelop the peak of the mountain.

Armed with a little more knowledge about the nature of floating clouds in Japanese poetry, let us now break down the Eishin-ryū tanka and examine it in a little more detail.

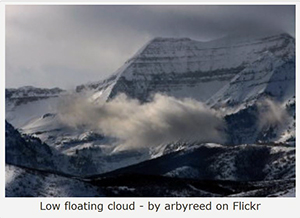

Low floating cloud - by arbyreed on Flickr

Iwata Norikazu notes in his book Koryū Iai no Hondō (Ski Journal, 2002) that Ukigumo is a waza of contrasts – highs and lows, peaks and troughs, grandness and subtlety. This not only describes the movements of the waza but also the feeling, and is, I feel, alluded to in the tanka above.

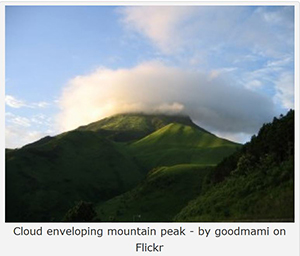

Cloud enveloping mountain peak - by goodmami on Flickr

The movement in this waza is complex and sees the practitioner moving back and forth, up and down: the depth of movement in this technique is another aspect that suggests the image of floating clouds. The practitioner is swift, and moves lightly and unpredictably in this waza. He is free to move, wholly unrestrained by the opponent.

This is only my basic interpretation, and it may well contain errors – as always, I leave it to those more knowledgeable and more experienced than myself to find the deeper meaning in the poem.